A signboard in venetian read “ here Venetian is besides spoken ” Venetian [ 7 ] [ 8 ] or Venetan [ 9 ] [ 10 ] ( łéngua vèneta [ e̯ŋgwa ˈvɛneta ] or vèneto [ ˈvɛneto ] ), is a Romance language spoken by Venetians in the northeastern of Italy, [ 11 ] largely in the Veneto region of Italy, where most of the five million inhabitants can understand it, centered in and around Venice, which carries the prestige dialect. It is sometimes spoken and frequently good sympathize outside Veneto, in Trentino, Friuli, the julian March, Istria, and some towns of Slovenia and Dalmatia ( Croatia ) by a surviving autochthonous venetian population, and Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Mexico by Venetians in the diaspora.

A signboard in venetian read “ here Venetian is besides spoken ” Venetian [ 7 ] [ 8 ] or Venetan [ 9 ] [ 10 ] ( łéngua vèneta [ e̯ŋgwa ˈvɛneta ] or vèneto [ ˈvɛneto ] ), is a Romance language spoken by Venetians in the northeastern of Italy, [ 11 ] largely in the Veneto region of Italy, where most of the five million inhabitants can understand it, centered in and around Venice, which carries the prestige dialect. It is sometimes spoken and frequently good sympathize outside Veneto, in Trentino, Friuli, the julian March, Istria, and some towns of Slovenia and Dalmatia ( Croatia ) by a surviving autochthonous venetian population, and Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Mexico by Venetians in the diaspora.

Reading: Venetian language – Wikipedia

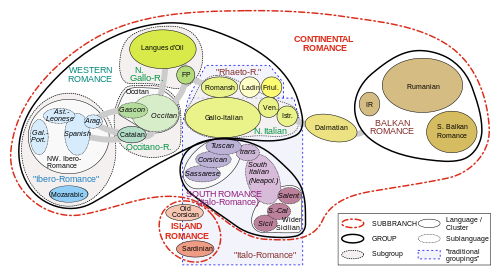

Although referred to as an italian dialect ( venetian : diałeto, italian : dialetto ) even by some of its speakers, Venetian is a freestanding terminology with many local varieties. Its precise locate within the Romance speech family remains controversial. Both Ethnologue and Glottolog group it into the Gallo-Italic branch. [ 8 ] [ 7 ] Devoto, Avolio and Treccani however reject a Gallo-Italic classification. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Tagliavini places it in the Italo-Dalmatian branch of languages. [ 15 ]

history [edit ]

Like all italian dialects in the Romance language class, Venetian is descended from Vulgar Latin and influenced by the italian language. venetian is attested as a written language in the thirteenth century. There are besides influences and parallelisms with Greek and Albanian in words such as piron ( fork ), inpirar ( to fork ), carega ( professorship ) and fanela ( T-shirt ). [ citation needed ] The speech enjoyed substantial prestige in the days of the Republic of Venice, when it attained the condition of a tongue franca in the Mediterranean Sea. celebrated Venetian-language authors include the playwrights Ruzante ( 1502–1542 ), Carlo Goldoni ( 1707–1793 ) and Carlo Gozzi ( 1720–1806 ). Following the old italian field tradition ( commedia dell’arte ), they used Venetian in their comedies as the speech of the park family. They are ranked among the foremost italian theatrical authors of all time, and plays by Goldoni and Gozzi are inactive performed today all over the universe. other luminary works in venetian are the translations of the Iliad by Giacomo Casanova ( 1725–1798 ) and Francesco Boaretti, the translation of the Divine Comedy ( 1875 ) by Giuseppe Cappelli and the poems of Biagio Marin ( 1891–1985 ). noteworthy excessively is a manuscript titled Dialogo de Cecco di Ronchitti da Bruzene in perpuosito de la stella Nuova attributed to Girolamo Spinelli, possibly with some supervision by Galileo Galilei for scientific details. [ 16 ] respective Venetian–Italian dictionaries are available in photographic print and on-line, including those by Boerio, [ 17 ] Contarini, [ 18 ] Nazari [ 19 ] and Piccio. [ 20 ] As a literary terminology, Venetian was overshadowed by Dante Alighieri ‘s tuscan dialect ( the best know writers of the Renaissance, such as Petrarch, Boccaccio and Machiavelli, were tuscan and wrote in the Tuscan lyric ) and languages of France like the Occitano-Romance languages and the langues d’oïl. even before the demise of the Republic, Venetian gradually ceased to be used for administrative purposes in privilege of the Tuscan-derived italian speech that had been proposed and used as a fomite for a common italian culture, powerfully supported by eminent venetian humanists and poets, from Pietro Bembo ( 1470–1547 ), a crucial number in the development of the italian lyric itself, to Ugo Foscolo ( 1778–1827 ). virtually all modern venetian speakers are diglossic with italian. The show situation raises questions about the speech ‘s survival. Despite holocene steps to recognize it, venetian remains far below the doorsill of inter-generational transfer with younger generations preferring standard Italian in many situations. The dilemma is far complicated by the ongoing large-scale arrival of immigrants, who only speak or learn criterion Italian. venetian ranch to early continents as a leave of mass migration from the Veneto area between 1870 and 1905, and between 1945 and 1960. venetian migrants created big Venetian-speaking communities in Argentina, Brazil ( see Talian ), and Mexico ( see Chipilo Venetian dialect ), where the terminology is still spoken today. In the nineteenth century large-scale immigration towards Trieste and Muggia extended the presence of the venetian linguistic process east. previously the dialect of Trieste had been a Ladin or Eastern friulian dialect known as Tergestino. This dialect became extinct as a result of venetian migration, which gave wax to the Triestino dialect of venetian talk there today. internal migrations during the twentieth hundred besides saw many Venetian-speakers settle in other regions of Italy, particularly in the Pontine Marshes of southerly Lazio where they populated raw towns such as Latina, Aprilia and Pomezia, forming there the alleged “ Venetian-Pontine “ community ( comunità venetopontine ). Currently, some firms have chosen to use venetian terminology in advertise as a celebrated beer did some years ago [ clarification needed ] ( Xe foresto solo el nome, “ only the diagnose is extraneous ” ). [ 21 ] [ dead link ] In other cases advertisements in Veneto are given a “ venetian flavor ” by adding a venetian word to standard italian : for exemplify an airline used the verb xe ( Xe sempre più grande, “ it is constantly bigger ” ) into an italian sentence ( the discipline venetian being el xe senpre pì grando ) [ 22 ] to advertise newfangled flights from Marco Polo Airport. [ citation needed ] In 2007, Venetian was given realization by the Regional Council of Veneto with regional jurisprudence no. 8 of 13 April 2007 “ Protection, enhancement and promotion of the linguistic and cultural heritage of Veneto ”. [ 23 ] Though the jurisprudence does not explicitly concede Venetian any official condition, it provides for Venetian as object of protection and enhancement, as an substantive component of the cultural, social, historical and civil identity of Veneto .

geographic distribution [edit ]

venetian is spoken chiefly in the italian regions of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and in both Slovenia and Croatia ( Istria, Dalmatia and the Kvarner Gulf ). [ citation needed ] Smaller communities are found in Lombardy ( Mantua ), Trentino, Emilia-Romagna ( Rimini and Forlì ), Sardinia ( Arborea, Terralba, Fertilia ), Lazio ( Pontine Marshes ), and once in Romania ( Tulcea ). It is besides spoken in North and South America by the descendants of italian immigrants. luminary examples of this are Argentina and Brazil, particularly the city of São Paulo and the Talian dialect spoken in the brazilian states of Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. In Mexico, the Chipilo Venetian dialect is spoken in the submit of Puebla and the town of Chipilo. The town was settled by immigrants from the Veneto region, and some of their descendants have preserved the language to this day. People from Chipilo have gone on to make satellite colonies in Mexico, specially in the states of Guanajuato, Querétaro, and State of Mexico. Venetian has besides survived in the state of Veracruz, where other italian migrants have settled since the late nineteenth century. The people of Chipilo preserve their dialect and call it chipileño, and it has been preserved as a random variable since the nineteenth hundred. The discrepancy of Venetian speak by the Cipiłàn ( Chipileños ) is northerly Trevisàn-Feltrìn-Belumàt. In 2009, the brazilian city of Serafina Corrêa, in the state of matter of Rio Grande do Sul, gave Talian a joint official status alongside Portuguese. [ 24 ] [ 25 ] Until the middle of the twentieth century, Venetian was besides spoken on the Greek Island of Corfu, which had long been under the convention of the Republic of Venice. furthermore, Venetian had been adopted by a large proportion of the population of Cephalonia, one of the ionian Islands, because the island was part of the Stato da Màr for about three centuries. [ 26 ]

categorization [edit ]

Chart of Romance languages based on geomorphologic and relative criteria. venetian is a Romance terminology and thus descends from Vulgar Latin. Its classification has constantly been controversial : According to Tagliavini, for exemplar, it is one of the Italo-Dalmatian languages and most close related to Istriot on the one pass and Tuscan – Italian on the other. [ 27 ] Some authors include it among the Gallo-Italic languages, [ 28 ] and according to others, it is not related to either one. [ 29 ] Although both Ethnologue and Glottolog group Venetian into the Gallo-Italic languages [ 8 ] [ 7 ], the linguists Giacomo Devoto and Francesco Avolio and the Treccani encyclopedia reject the Gallo-Italic classification. [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Although the lyric region is surrounded by Gallo-Italic languages, Venetian does not share some traits with these contiguous neighbors. Some scholars stress Venetian ‘s characteristic miss of Gallo-Italic traits ( agallicità ) [ 33 ] or traits found far afield in Gallo-Romance languages ( e.g. Occitan, French, Franco-Provençal ) [ 34 ] or the rhaeto-romance languages ( e.g. friulian, Romansh ). For example, Venetian did not undergo vowel round off or nasalization, palatalize /kt/ and /ks/, or develop rising diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/, and it preserved final examination syllables, whereas, as in italian, venetian diphthongization occurs in historically open syllables. On the other bridge player, it is worth noting that Venetian does share many other traits with its surrounding Gallo-Italic languages, like question clitics, compulsory unstressed subject pronouns ( with some exceptions ), the “ to be behind to ” verbal construction to express the continuous aspect ( “ El xé drìo magnàr ” = He is eating, light. he is behind to eat ) and the absence of the absolute past tense angstrom well as of pair consonants. [ 35 ] In addition, Venetian has some unique traits which are shared by neither Gallo-Italic, nor Italo-Dalmatian languages, such as the use of the impersonal passive forms and the habit of the aide verb “ to have ” for the automatic voice ( both traits shared with german ). [ 36 ] modern Venetian is not a close relative of the extinct Venetic speech spoken in Veneto before Roman expansion, although both are aryan, and Venetic may have been an Italic language, like Latin, the ancestor of venetian and most other languages of Italy. The earlier Venetic people gave their appoint to the city and region, which is why the mod linguistic process has a similar name .

Chart of Romance languages based on geomorphologic and relative criteria. venetian is a Romance terminology and thus descends from Vulgar Latin. Its classification has constantly been controversial : According to Tagliavini, for exemplar, it is one of the Italo-Dalmatian languages and most close related to Istriot on the one pass and Tuscan – Italian on the other. [ 27 ] Some authors include it among the Gallo-Italic languages, [ 28 ] and according to others, it is not related to either one. [ 29 ] Although both Ethnologue and Glottolog group Venetian into the Gallo-Italic languages [ 8 ] [ 7 ], the linguists Giacomo Devoto and Francesco Avolio and the Treccani encyclopedia reject the Gallo-Italic classification. [ 30 ] [ 31 ] [ 32 ] Although the lyric region is surrounded by Gallo-Italic languages, Venetian does not share some traits with these contiguous neighbors. Some scholars stress Venetian ‘s characteristic miss of Gallo-Italic traits ( agallicità ) [ 33 ] or traits found far afield in Gallo-Romance languages ( e.g. Occitan, French, Franco-Provençal ) [ 34 ] or the rhaeto-romance languages ( e.g. friulian, Romansh ). For example, Venetian did not undergo vowel round off or nasalization, palatalize /kt/ and /ks/, or develop rising diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/, and it preserved final examination syllables, whereas, as in italian, venetian diphthongization occurs in historically open syllables. On the other bridge player, it is worth noting that Venetian does share many other traits with its surrounding Gallo-Italic languages, like question clitics, compulsory unstressed subject pronouns ( with some exceptions ), the “ to be behind to ” verbal construction to express the continuous aspect ( “ El xé drìo magnàr ” = He is eating, light. he is behind to eat ) and the absence of the absolute past tense angstrom well as of pair consonants. [ 35 ] In addition, Venetian has some unique traits which are shared by neither Gallo-Italic, nor Italo-Dalmatian languages, such as the use of the impersonal passive forms and the habit of the aide verb “ to have ” for the automatic voice ( both traits shared with german ). [ 36 ] modern Venetian is not a close relative of the extinct Venetic speech spoken in Veneto before Roman expansion, although both are aryan, and Venetic may have been an Italic language, like Latin, the ancestor of venetian and most other languages of Italy. The earlier Venetic people gave their appoint to the city and region, which is why the mod linguistic process has a similar name .

regional variants [edit ]

The main regional varieties and subvarieties of venetian terminology :

All these variants are mutually apprehensible, with a minimum 92 % in common among the most divergent ones ( Central and Western ). modern speakers reportedly can calm understand venetian textbook from the fourteenth hundred to some extent. other noteworthy variants are :

grammar [edit ]

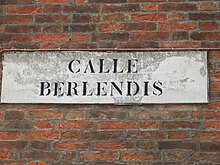

nizioléto) in Venice using Venetian calle, as opposed to the Italian via A street sign ( ) in Venice using venetian, as opposed to the italian

nizioléto) in Venice using Venetian calle, as opposed to the Italian via A street sign ( ) in Venice using venetian, as opposed to the italian

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| el gato graso | el gato graso | il gatto grasso | the fat (male) cat |

| la gata grasa | ła gata grasa | la gatta grassa | the fat (female) cat |

| i gati grasi | i gati grasi | i gatti grassi | the fat (male) cats |

| le gate grase | łe gate grase | le gatte grasse | the fat (female) cats |

In recent studies on venetian variants in Veneto, there has been a tendency to write the alleged “ evanescent L ” as ⟨ł⟩. While it may help novitiate speakers, Venetian was never written with this letter. In this article, this symbol is used alone in Veneto dialects of venetian linguistic process. It will suffice to know that in venetian language the letter L in word-initial and intervocalic positions normally becomes a “ palatal allomorph ”, and is scantily pronounced. [ 37 ] No native Venetic words seem to have survived in award venetian, but there may be some traces left in the morphology, such as the morpheme – esto / asto / isto for the by participle, which can be found in Venetic inscriptions from about 500 BC :

- Venetian: Mi A go fazesto (“I have done”)

- Venetian Italian: Mi A go fato

- Standard Italian: Io ho fatto

excess subject pronouns [edit ]

A peculiarity of venetian grammar is a “ semi-analytical ” verbal flexion, with a compulsory “ clitic subject pronoun ” before the verb in many sentences, “ echoing ” the subject as an ending or a weak pronoun. Independent/emphatic pronouns ( e.g. ti ), on the contrary, are optional. The clitic topic pronoun ( te, el/ła, i/łe ) is used with the 2nd and 3rd person singular, and with the 3rd person plural. This feature may have arisen as a recompense for the fact that the 2nd- and 3rd-person inflections for most verbs, which are silent clear-cut in italian and many other Romance languages, are identical in Venetian .

| Venetian | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|

| Mi go | Io ho | I have |

| Ti ti ga | Tu hai | You have |

| Venetian | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|

| Mi so | Io sono | I am |

| Ti ti xe | Tu sei | You are |

The Piedmontese language besides has clitic subject pronouns, but the rules are slightly different. The routine of clitics is peculiarly visible in farseeing sentences, which do not always have pass intonational breaks to easily tell apart vocative and imperative mood in sharp commands from exclamations with “ shouted indicative ”. For example, in venetian the clitic el marks the indicative verb and its masculine curious submit, otherwise there is an imperative preceded by a vocative. Although some grammars regard these clitics as “ excess ”, they actually provide specific extra information as they mark number and gender, frankincense providing number-/gender- agreement between the subjugate ( randomness ) and the verb, which does not inevitably show this information on its endings .

interrogative inflection [edit ]

venetian besides has a extra interrogative verbal flexure used for direct questions, which besides incorporates a pleonastic pronoun :

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti geristu sporco? | (Ti) jèristu onto? or (Ti) xèrito spazo? |

(Tu) eri sporco? | Were you dirty? |

| El can, gerilo sporco? | El can jèreło onto? or Jèreło onto el can ? |

Il cane era sporco? | Was the dog dirty? |

| Ti te gastu domandà? | (Ti) te sito domandà? | (Tu) ti sei domandato? | Did you ask yourself? |

aide verb [edit ]

reflexive pronoun tenses use the accessory verb avér ( “ to have ” ), as in English, the North Germanic languages, Catalan, Spanish, Romanian and Neapolitan ; alternatively of èssar ( “ to be ” ), which would be normal in italian. The past participle is invariable, unlike italian :

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti ti te ga lavà | (Ti) te te à/gà/ghè lavà | (Tu) ti sei lavato | You washed yourself |

| (Lori) i se ga desmissià | (Lori) i se gà/à svejà | (Loro) si sono svegliati | They woke up |

Continuing action [edit ]

Another curio of the language is the consumption of the phrase eser drìo ( literally, “ to be behind ” ) to indicate continuing natural process :

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Me pare, el ze drìo parlàr | Mé pare ‘l ze drìo(invià) parlàr | Mio padre sta parlando | My father is speaking |

Another progressive form in some venetian dialects uses the construction èsar łà che ( ignite. “ to be there that ” ) :

- Venetian dialect: Me pare l’è là che’l parla (lit. “My father he is there that he speaks”).

The use of progressive tenses is more permeant than in italian ; e.g .

- English: “He wouldn’t have been speaking to you”.

- Venetian: No’l sarìa miga sta drio parlarte a ti.

That construction does not occur in italian : *Non sarebbe mica stato parlandoti is not syntactically valid .

Subordinate clauses [edit ]

Subordinate clauses have double introduction ( “ whom that ”, “ when that ”, “ which that ”, “ how that ” ), as in Old English :

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mi so de chi che ti parli | So de chi che te parli | So di chi parli | I know who you are talking about |

As in early Romance languages, the subjunctive mood mood is wide used in subordinate clauses .

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mi credeva che’l fuse … | Credéa/évo che’l fuse … | Credevo che fosse … | I thought he was … |

phonology [edit ]

Consonants [edit ]

Some dialects of venetian have certain sounds not introduce in italian, such as the interdental aphonic fricative consonant [ θ ], much spelled with ⟨ç⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨zh⟩, or ⟨ž⟩, and like to English th in thing and thought. This sound occurs, for example, in çéna ( “ supper ”, besides written zhena, žena ), which is pronounced the like as castilian spanish cena ( which has the lapp entail ). The breathed interdental fricative occurs in Bellunese, north-Trevisan, and in some Central venetian rural areas around Padua, Vicenza and the mouth of the river Po. Because the pronunciation variant [ θ ] is more typical of older speakers and speakers living outside of major cities, it has come to be socially stigmatized, and most speakers now use [ s ] or [ triiodothyronine ] rather of [ θ ]. In those dialects with the pronunciation [ south ], the healthy has fallen together with ordinary ⟨s⟩, and so it is not rare to plainly write ⟨s⟩ ( or ⟨ss⟩ between vowels ) rather of ⟨ç⟩ or ⟨zh⟩ ( such as sena ). similarly some dialects of Venetian besides have a voiced interdental fricative consonant [ ð ], often written ⟨z⟩ ( as in el pianze ‘he cries ‘ ) ; but in most dialects this phone is nowadays pronounce either as [ dz ] ( italian voiced-Z ), or more typically as [ z ] ( italian voiced-S, written ⟨x⟩, as in el pianxe ) ; in a few dialects the sound appears as [ vitamin d ] and may therefore be written rather with the letter ⟨d⟩, as in el piande. Some varieties of Venetian besides distinguish an ordinary [ liter ] vs. a weakened or lenited ( “ evanescent ” ) ⟨l⟩, which in some orthographic norms is indicated with the letter ⟨ ł ⟩ ; [ 38 ] in more conservative dialects, however, both ⟨l⟩ and ⟨ł⟩ are merged as ordinary [ liter ]. In those dialects that have both types, the accurate phonetic realization of ⟨ł⟩ depends both on its phonological environment and on the dialect of the speaker. typical realizations in the region of Venice include a voice velar approximant or glide [ ɰ ] ( normally described as about like an “ vitamin e ” and so much spelled as ⟨e⟩ ), when ⟨ł⟩ is adjacent ( entirely ) to back vowels ( ⟨a oxygen u⟩ ), vs. a null realization when ⟨ł⟩ is adjacent to a front vowel ( ⟨i e⟩ ). In dialects far inland ⟨ł⟩ may be realized as a partially vocalize ⟨l⟩. frankincense, for example, góndoła ‘gondola ‘ may sound like góndoea [ ˈɡoŋdoɰa ], góndola [ ˈɡoŋdola ], or góndoa [ ˈɡoŋdoa ]. In dialects having a nothing realization of intervocalic ⟨ł⟩, although pairs of words such as scóła, “ school ” and scóa, “ sweep ” are homophonous ( both being pronounced [ ˈskoa ] ), they are hush distinguished orthographically. venetian, like spanish, does not have the pair consonants characteristic of standard Italian, Tuscan, Neapolitan and other languages of southerly Italy ; frankincense italian fette ( “ slices ” ), palla ( “ ball ” ) and penna ( “ pen ” ) equate to féte, bała, and péna in Venetian. The masculine singular noun ending, corresponding to -o / -e in italian, is frequently unpronounced in venetian after continuants, peculiarly in rural varieties : italian pieno ( “ full ” ) corresponds to Venetian pien, italian altare to venetian altar. The extent to which final vowels are deleted varies by dialect : the central–southern varieties delete vowels lone after / normality /, whereas the northern variety erase vowels besides after dental stops and velars ; the eastern and western varieties are in between these two extremes. The velar rhinal [ ŋ ] ( the final sound in English “ song ” ) occurs frequently in Venetian. A word-final / newton / is always velarized, which is particularly obvious in the pronunciation of many local Venetian surnames that end in ⟨n⟩, such as Marin [ maˈɾiŋ ] and Manin [ maˈniŋ ], arsenic well as in park venetian words such as man ( [ ˈmaŋ ] “ hand ” ), piron ( [ piˈɾoŋ ] “ fork ” ). furthermore, Venetian constantly uses [ ŋ ] in consonant clusters that start with a nasal, whereas italian only uses [ ŋ ] before velar stops : e.g. [ kaŋˈtaɾ ] “ to sing ”, [ iŋˈvɛɾno ] “ winter ”, [ ˈoŋzaɾ ] “ to anoint ”, [ ɾaŋˈdʒaɾse ] “ to cope with ”. [ 39 ] Speakers of italian generally lack this sound and normally substitute a dental [ normality ] for final Venetian [ ŋ ], changing for example [ maˈniŋ ] to [ maˈnin ] and [ maˈɾiŋ ] to [ maˈrin ].

Read more: 2015–16 Liverpool F.C. season – Wikipedia

Vowels [edit ]

An stressed á can besides be pronounced as [ ɐ ]. An intervocalic / uranium / can be pronounced as a [ tungsten ] voice .

prosody [edit ]

While written Venetian looks like to italian, it sounds very different, with a discrete lilt cadence, about musical. Compared to Italian, in venetian syllabic rhythm are more evenly timed, accents are less mark, but on the other hand tonal transition is much wide-eyed and melodic curves are more intricate. Stressed and unstressed syllables sound about the same ; there are no hanker vowels, and there is no accordant lengthen. Compare the italian prison term va laggiù con lui [ val.ladˌd͡ʒuk.konˈluː.i ] “go there with him” ( all long/heavy syllables but final ) with venetian va là zo co lu [ va.laˌzo.koˈlu ] ( all short/light syllables ) .

Sample etymological vocabulary [edit ]

As a direct descent of regional talk Latin, venetian dictionary derives its vocabulary substantially from Latin and ( in more late times ) from Tuscan, so that most of its words are cognate with the correspond words of italian. venetian includes however many words derived from other sources ( such as Greek, Gothic, and German ), and has preserved some Latin words not used to the like extent in italian, resulting in many words that are not connate with their equivalent words in italian, such as :

| English | Italian | Venetian (DECA) | Venetian word origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| today | oggi | uncò, ‘ncò, incò, ancò, ancúo, incoi | from Latin hunc + hodie |

| pharmacy | farmacia | apotèca | from Ancient Greek ἀποθήκηapothḗkē) |

| to drink | bere | trincàr | from German trinken “to drink” |

| apricot | albicocca | armelín | from Latin armenīnus |

| to bore | dare noia, seccare | astiàr | from Gothic ???????, haifsts |

| peanuts | arachidi | bagígi | from Arabic habb-ajiz |

| to be spicy hot | essere piccante | becàr | from Italian beccare, literally “to peck” |

| spaghetti | vermicello, spaghetti | bígolo | from Latin (bom)byculus |

| eel | anguilla | bizàto, bizàta | from Latin bestia “beast”, compare also Italian biscia, a kind of snake |

| snake | serpente | bísa, bíso | from Latin bestia “beast”, compare also Ital. biscia, a kind of snake |

| peas | piselli | bízi | related to the Italian word |

| lizard | lucertola | izarda, rizardola | from Latin lacertus, same origin as English lizard |

| to throw | tirare | trar via | local cognate of Italian tirare |

| fog | nebbia foschia | calígo | from Latin caligo |

| corner/side | angolo/parte | cantón | from Latin cantus |

| find | trovare | catàr | from Latin *adcaptare |

| chair | sedia | caréga, trón | from Latin cathedra and thronus (borrowings from Greek) |

| hello, goodbye | ciao | ciao | from Venetian s-ciao “slave”, from Medieval Latin sclavus |

| to catch, to take | prendere | ciapàr | from Latin capere |

| when (non-interr.) | quando | co | from Latin cum |

| to kill | uccidere | copàr | from Old Italian accoppare, originally “to behead” |

| miniskirt | minigonna | carpéta | compare English carpet |

| skirt | sottana | còtoła | from Latin cotta, “coat, dress” |

| T-shirt | maglietta | fanèla | borrowing from Greek |

| drinking glass | bicchiere | gòto | from Latin guttus, “cruet” |

| Big | grande | grosi | From German “grosse” |

| exit | uscita | insía | from Latin in + exita |

| I | io | mi | from Latin me (“me”, accusative case); Italian io is derived from the Latin nominative form ego |

| too much | troppo | masa | from Greek μᾶζαmâza) |

| to bite | mordere | morsegàr, smorsegàr | deverbal derivative, from Latin morsus “bitten”, compare Italian morsicare |

| moustaches | baffi | mustaci | from Greek μουστάκιmoustaki) |

| cat | gatto | munín, gato, gateo | perhaps onomatopoeic, from the sound of a cat’s meow |

| big sheaf | grosso covone | meda | from messe, mietere, compare English meadow |

| donkey | asino | muso | from Latin almutia “horses eye binders (cap)” (compare Provençal almussa, French aumusse) |

| bat | pipistrello | nòtoła, notol, barbastrío, signàpoła | derived from not “night” (compare Italian notte) |

| rat | ratto | pantegàna | from Slovene podgana |

| beat, cheat, sexual intercourse | imbrogliare, superare in gara, amplesso | pinciàr | from French pincer (compare English pinch) |

| fork | forchetta | pirón | from Greek πιρούνιpiroúni) |

| dandelion | tarassaco | pisalet | from French pissenlit |

| truant | marinare scuola | plao far | from German blau machen |

| apple | mela | pomo/pón | from Latin pomus |

| to break, to shred | strappare | zbregàr | from Gothic ??????brikan), related to English to break and German brechen |

| money | denaro soldi | schèi | from German Scheidemünze |

| grasshopper | cavalletta | saltapaiusc | from salta “hop” + paiusc “grass” (Italian paglia) |

| squirrel | scoiattolo | zgiràt, scirata, skirata | Related to Italian word, probably from Greek σκίουροςskíouros) |

| spirit from grapes, brandy | grappa acquavite | znjapa | from German Schnaps |

| to shake | scuotere | zgorlàr, scorlàr | from Latin ex + crollare |

| rail | rotaia | sina | from German Schiene |

| tired | stanco | straco | from Lombard strak |

| line, streak, stroke, strip | linea, striscia | strica | from the proto-Germanic root *strik, related to English streak, and stroke (of a pen). Example: Tirar na strica “to draw a line”. |

| to press | premere, schiacciare | strucàr | from proto-Germanic *þrukjaną (‘to press, crowd’) through the Gothic or Langobardic language, related to Middle English thrucchen (“to push, rush”), German drücken (‘to press’), Swedish trycka. Example: Struca un tasto / boton “Strike any key / Press any button”. |

| to whistle | fischiare | supiàr, subiàr, sficiàr, sifolàr | from Latin sub + flare, compare French siffler |

| to pick up | raccogliere | tòr su | from Latin tollere |

| pan | pentola | técia, téia, tegia | from Latin tecula |

| lad, boy | ragazzo | tozàt(o) (toxato), fio | from Italian tosare, “to cut someone’s hair” |

| lad, boy | ragazzo | puto, putèło, putełeto, butèl | from Latin puer, putus |

| lad, boy | ragazzo | matelot | perhaps from French matelot, “sailor” |

| cow | mucca, vacca | vaca | from Latin vacca |

| gun | fucile-scoppiare | sciop, sciòpo, sciopàr, sciopón | from Latin scloppum (onomatopoeic) |

| track path | sentiero | troi | from Latin trahere, “to draw, pull”, compare English track |

| to worry | preoccuparsi, vaneggiare | dzavariàr, dhavariàr, zavariàr | from Latin variare |

Spelling systems [edit ]

traditional arrangement [edit ]

venetian does not have an official compose system, but it is traditionally written using the Latin script — sometimes with certain extra letters or diacritics. The basis for some of these conventions can be traced to Old Venetian, while others are strictly modern innovations. Medieval textbook, written in Old Venetian, include the letters ⟨x⟩, ⟨ç⟩ and ⟨z⟩ to represent sounds that do not exist or have a different distribution in italian. specifically :

- The letter ⟨x⟩ was often employed in words that nowadays have a voiced z/xylophone); for instance ⟨x⟩ appears in words such as raxon, Croxe, caxa (“reason”, “(holy) Cross” and “house”). The precise phonetic value of ⟨x⟩ in Old Venetian texts remains unknown, however.

- The letter ⟨z⟩ often appeared in words that nowadays have a varying voiced pronunciation ranging from z/dz/ð/d/zo “down” may represent any of /zo, dzo, ðo/ or even /do/, depending on the dialect; similarly zovena “young woman” could be any of /ˈzovena/, /ˈdzovena/ or /ˈðovena/, and zero “zero” could be /ˈzɛro/, /ˈdzɛro/ or /ˈðɛro/.

- Likewise, ⟨ç⟩ was written for a voiceless sound which now varies, depending on the dialect spoken, from s/ts/θ/dolçe “sweet”, now /ˈdolse ~ ˈdoltse ~ ˈdolθe/, dolçeça “sweetness”, now /dolˈsesa ~ dolˈtsetsa ~ dolˈθeθa/, or sperança “hope”, now /speˈransa ~ speˈrantsa ~ speˈranθa/.

The use of letters in medieval and early advanced text was not, however, entirely coherent. In particular, as in other northern italian languages, the letters ⟨z⟩ and ⟨ç⟩ were often used interchangeably for both voiced and breathed sounds. Differences between earlier and mod pronunciation, divergences in pronunciation within the advanced Venetian-speaking region, differing attitudes about how closely to model spelling on italian norms, arsenic well as personal preferences, some of which reflect sub-regional identities, have all hindered the adoption of a single unified spell system. [ 41 ] however, in exercise, most spell conventions are the same as in italian. In some early mod texts letter ⟨x⟩ become limited to word-initial position, as in xe ( “ is ” ), where its consumption was ineluctable because italian spell can not represent / z / there. In between vowels, the distinction between / s / and / z / was normally indicated by double ⟨ss⟩ for the former and one ⟨s⟩ for the latter. For model, basa was used to represent /ˈbaza/ ( “ he/she kisses ” ), whereas bassa represented /ˈbasa/ ( “ broken ” ). ( Before consonants there is no contrast between / s / and / z /, as in italian, so a unmarried ⟨s⟩ is always used in this circumstance, it being understood that the ⟨s⟩ will agree in voicing with the trace consonant. For example, ⟨st⟩ represents lone /st/, but ⟨sn⟩ represents /zn/. ) traditionally the letter ⟨z⟩ was equivocal, having the lapp values as in italian ( both voiced and unvoiced affricates / dz / and / ts / ). Nevertheless, in some books the two pronunciations are sometimes distinguished ( in between vowels at least ) by using double over ⟨zz⟩ to indicate / t / ( or in some dialects / θ / ) but a single ⟨z⟩ for / dz / ( or / ð /, / d / ). In more recent practice the use of ⟨x⟩ to represent / z /, both in word-initial equally well as in intervocalic context, has become increasingly common, but no wholly uniform convention has emerged for the representation of the voiced vs. breathed affricates ( or interdental fricatives ), although a fall to using ⟨ç⟩ and ⟨z⟩ remains an option under circumstance. Regarding the spell of the vowel sounds, because in Venetian, as in italian, there is no contrast between tense and lax vowels in unstressed syllables, the orthographic grave and acute accents can be used to mark both stress and vowel timbre at the like time : à / a /, á / ɐ /, è / ɛ /, é / einsteinium /, í / iodine /, ò / ɔ /, ó / o /, ú / uracil /. Different orthographic norms prescribe slightly different rules for when stress vowels must be written with accents or may be left overlooked, and no one organization has been accepted by all speakers. venetian allows the consonant cluster /stʃ/ ( not present in italian ), which is sometimes written ⟨s-c⟩ or ⟨s’c⟩ before i or e, and ⟨s-ci⟩ or ⟨s’ci⟩ before other vowels. Examples include s-ciarir ( italian schiarire, “ to clear up ” ), s-cèt ( schietto, “ plain clear ” ), s-ciòp ( schioppo, “ grease-gun ” ) and s-ciao ( schiavo, “ [ your ] servant ”, ciao, “ hello ”, “ adieu ” ). The hyphen or apostrophe is used because the combination ⟨sc ( iodine ) ⟩ is conventionally used for the / ʃ / sound, as in italian spell ; e.g. scèmo ( scemo, “ stupid ” ) ; whereas ⟨sc⟩ before a, o and u represents /sk/ : scàtoła ( scatola, “ box ” ), scóndar ( nascondere, “ to hide ” ), scusàr ( scusare, “ to forgive ” ) .

Proposed systems [edit ]

recently there have been attempts to standardize and simplify the script by reusing older letters, e.g. by using ⟨x⟩ for [ z ] and a single ⟨s⟩ for [ sulfur ] ; then one would write baxa for [ ˈbaza ] ( “ [ third person singular ] kisses ” ) and basa for [ ˈbasa ] ( “ broken ” ). Some authors have continued or resumed the consumption of ⟨ç⟩, but alone when the resulting son is not excessively different from the italian orthography : in modern venetian writings, it is then easier to find words as çima and çento, preferably than força and sperança, tied though all these four words display the same phonological variation in the position marked by the letter ⟨ç⟩. Another holocene convention is to use ⟨ ł ⟩ ( in put of older ⟨ ł ⟩ ) for the “ soft ” l, to allow a more mix orthography for all variants of the terminology. however, in cattiness of their theoretical advantages, these proposals have not been identical successful outside of academic circles, because of regional variations in pronunciation and incompatibility with existing literature. More recently, on December 14, 2017, the Modern International Manual of Venetian Spelling has been approved by the new Commission for Spelling of 2010. It has been translated in three languages ( italian, venetian and English ) and it exemplifies and explains every unmarried letter and every healthy of the venetian terminology. The graphic emphasizing and punctuation systems are added as corollaries. Overall, the system has been greatly simplified from former ones to allow both italian and alien speakers to learn and understand the venetian spell and rudiment in a more straightforward way. [ 42 ] The venetian speakers of Chipilo use a system based on spanish orthography, tied though it does not contain letters for [ j ] and [ θ ]. The american linguist Carolyn McKay proposed a write arrangement for that random variable based entirely on the italian rudiment. however, the system was not very popular .

Orthographies comparison [edit ]

| [IPA] | DECA [43] | classic | Brunelli | Chipilo | Talian | Latin origin [44] | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ˈa/ | à | à | à | á | à | ă /a/, ā /aː/ | ||

| /b/ | b | b | b | b, v | b | b /b/, -p- /p/ | barba (beard, uncle) from barba | |

| /k/ | + a \ o \ u | c | c | c | c | c | c /k/, cc /kː/, tc /tk/, xc /ksk/ | poc (little) from paucus |

| + i \ e \ y \ ø | ch | ch | ch | qu | ch | ch /kʰ/, qu /kʷ/ | chiete (quiet) from quiētem | |

| (between vowels) | c(h) | cc(h) | c(h) | – | c(h) | |||

| /ts/~/θ/~/s/ | + a \ o \ u | ts~th~s | ç, [z] | ç | -~zh~s | – | ti /tj/, th /tʰ/ | |

| + i \ e \ y \ ø | c, [z] | c /c/, ti /tj/, th /tʰ/, tc /tk/, xc /ksk/ | ||||||

| (between vowels) | zz | ti /tj/, th /tʰ/ | ||||||

| /s/ | (before a vowel) | s | s | s | s (z) | s | s /s/, ss /sː/, sc /sc/, ps /ps/, x /ks/ | supiar (to whistle) from sub-flare |

| (between vowels) | ss | ss | casa (cash des) from capsa | |||||

| (before unvoiced consonant) | s | s | ||||||

| /tʃ/ | + a \ o \ u | ci | chi | ci | ch | ci | cl /cl/ | sciào (slave) from sclavus |

| + i \ e \ y \ ø | c | c | c | ceza (church) from ecclēsia | ||||

| (between vowels) | c(i) | cchi | c(i) | c(i) | ||||

| (ending of word) | c’ | cch’ | c’ | ch | c’ | moc’ (snot) from *mucceus | ||

| /d/ | d | d | d | d | d | d /d/, -t- /t/, (g /ɟ/, di /dj/, z /dz/) | cadena (chain) from catēna | |

| /ˈɛ/ | è | è | è | è | è | ĕ /ɛ/, ae /ae̯/ | ||

| /ˈe/ | é | é | é | é | é | ē /ɛː/, ĭ /i/, oe /oe̯/ | pévare (pepper) from piper | |

| /f/ | – | f | f | f | f | f | f /f/, ff /fː/, pp /pː/, ph /pʰ/ | finco (finch) from fringilla |

| (between vowels) | ff | |||||||

| /ɡ/ | + a \ o \ u | g | g | g | g | g | g /ɡ/, -c- /k/, ch /kʰ | ruga (bean weevil) from brūchus |

| + i \ e \ y \ ø | gh | gh | gh | gu | gh | gu /ɡʷ/, ch /kʰ/ | ||

| /dz/~/ð/~/z/ | + a \ o \ u | dz~dh~z | z | z | -~d~x | – | z /dz/, di /dj/ | dzorno from diurnus |

| + i \ e \ y \ ø | z /dz/, g /ɟ/, di /dj/ | dzendziva (gum) from gingiva | ||||||

| /z/ | (before a vowel) | z | x | x | x | z | ?, (z /dz/, g /ɉ/, di /dj/) | el ze (he is) from ipse est |

| (between vowels) | s | s | -c- /c/, -s- /s/, x /ɡz/, (z /dz/, g /ɉ/, di /dj/) | paze (peace) from pāx, pācis | ||||

| (before voiced consonant) | s | s | s | s- /s/, x /ɡz/, (z /dz/, g /ɉ/, di /dj/) | zgorlar (to shake) from ex-crollare | |||

| /dʒ/ | + a \ o \ u | gi | ghi | gi | gi | j | gl /ɟl/ | giatso (ice) from glaciēs |

| + i \ e \ y \ ø | g | g | g | gi | giro (dormouse) from glīris | |||

| /j/~/dʒ/ | j~g(i) | g(i) | j | – | j | i /j/, li /lj/ | ajo / agio (garlic) from ālium | |

| /j/ | j, i | j, i | i | y, i | i | i /j/ | ||

| /ˈi/ | í | í | í | í | í | ī /iː/, ȳ /yː/ | fio (son) from fīlius | |

| – | h | h | h | h | h | h /ʰ/ | màchina (machine) from māchina | |

| /l/ | l | l | l | l | l | l /l/ | ||

| /e̯/~/ɰ/~- | ł | l | ł | – | – | l /l/ | ||

| /l.j/~/l.dʒ/ | li~g(i) | li | lj | ly | li | li /li/, /lj/ | ||

| /m/ | (before vowels) | m | m | m | m | m | m /m/ | |

| (at the end of the syllable) | m’ | – | m’ | m’ | m’ | m /m/ | ||

| /n/ | (before vowels) | n | n | n | n | n | n /n/ | |

| (at the end of the syllable) | n’ / ‘n | – | n’ | n’ | n’ | n /n/ | don’ (we go) from *andamo | |

| /ŋ/ | (before vowels) | n- | – | n- | n- | n- | m /m/, n /ɱ~n̪~n~ŋ/, g /ŋ/ | |

| (at the end of the syllable) | n / n- | m, n | n | n | n | m /m/, n /ɱ~n̪~n~ŋ/, g /ŋ/ | don (we went) from andavamo | |

| /m.j/~/m.dʒ/ | m’j~m’g(i) | (mi) | m’j | m’y | mi | |||

| /n.j/~/n.dʒ/ | n’j~n’g(i) | (ni) | n’j | n’y | ni | ni /ni/, ni /nj/ | ||

| /ŋ.j/~/ŋ.dʒ/ | ni~ng(i) | ni | n-j | ny | n-j | ni /n.j/ | ||

| /ɲ/ | nj | gn | gn | ñ | gn | gn /ŋn/, ni /nj/ | cunjà (brother-in-law) from cognātus | |

| /ˈɔ/ | ò | ò | ò | ò | ò | ŏ /ɔ/ | ||

| /ˈo/ | ó | ó | ó | ó | ó | ō /ɔː/, ŭ /u/ | ||

| /p/ | – | p | p | p | p | p | p /p/, pp /pː/ | |

| (between vowels) | pp | |||||||

| /r/ | r | r | r | r | r | r /r/ | ||

| /r.j/~/r.dʒ/ | ri~rg(i) | (ri) | rj | ry | rj | |||

| /t/ | – | t | t | t | t | t | t /t/, tt /tː/, ct /kt/, pt /pt/ | sète (seven) from septem |

| (between vowels) | tt | |||||||

| /ˈu/ | ú | ú | ú | ú | ú | ū /uː/ | ||

| /w/ | u | u | u | u | u | u /w/ | ||

| /v/ | v | v | v | v | v | u /w/, b /b/, -f- /f/, -p- /p/ | ||

| /ˈɐ/~/ˈʌ/~/ˈɨ/ | â / á | – | – | – | – | ē /ɛː/, an /ã/ | stâla (star) from stēlla | |

| /ˈø/ | (ø) | (oe) | (o) | – | – | |||

| /ˈy/ | (y / ý) | (ue) | (u) | – | – | |||

| /h/ | h / fh | – | – | – | – | f /f/ | hèr (iron) from ferrus | |

| /ʎ/ | lj | – | – | – | – | li /lj/ | batalja (battle) from battālia | |

| /ʃ/ | sj | – | (sh) | – | – | s /s/ | ||

| /ʒ/ | zj | – | (xh) | – | – | g /ɡ/ | ||

Sample textbook [edit ]

Ruzante returning from war [edit ]

The follow sample, in the old dialect of Padua, comes from a play by Ruzante ( Angelo Beolco ), titled Parlamento de Ruzante che iera vegnù de campo ( “ Dialogue of Ruzante who came from the battlefield ”, 1529 ). The character, a peasant returning home from the war, is expressing to his ally Menato his relief at being still alive :

| Orbéntena, el no serae mal star in campo per sto robare, se ‘l no foesse che el se ha pur de gran paure. Càncaro ala roba! A’ son chialò mi, ala segura, e squase che no a’ no cherzo esserghe gnan. … Se mi mo’ no foesse mi? E che a foesse stò amazò in campo? E che a foesse el me spirito? Lo sarae ben bela. No, càncaro, spiriti no magna. |

actually, it would not be that bad to be in the battlefield plunder, were it not that one gets besides big scares. Damn the loot ! I am right hera, in safety, and about ca n’t believe I am. … And if I were not me ? And if I had been killed in battle ? And if I were my touch ? That would be just capital. No, damn, ghosts do n’t eat . |

Discorso de Perasto [edit ]

The following sample distribution is taken from the Perasto Speech ( Discorso de Perasto ), given on August 23, 1797 at Perasto, by venetian Captain Giuseppe Viscovich, at the last lower of the flag of the Venetian Republic ( nicknamed the “ Republic of Saint Mark “ ) .

| Par trezentosetantasete ani le nostre sostanse, el nostro sangue, le nostre vite le xè sempre stàe par Ti, S. Marco; e fedelisimi senpre se gavemo reputà, Ti co nu, nu co Ti, e sempre co Ti sul mar semo stài lustri e virtuosi. Nisun co Ti ne gà visto scanpar, nisun co Ti ne gà visto vinti e spaurosi! |

For three hundred and seventy seven years our bodies, our blood our lives have constantly been for You, St. Mark ; and very congregation we have always thought ourselves, You with us, we with You, And always with You on the sea we have been celebrated and pure. No one has seen us with You flee, No one has seen us with You defeated and fearful ! |

Francesco Artico [edit ]

The pursue is a contemporary textbook by Francesco Artico. The aged narrator is recalling the church choir singers of his young, who, needle to say, sing much better than those of today ( see the full original text with audio ) :

| Sti cantori vèci da na volta, co i cioéa su le profezie, in mezo al coro, davanti al restèl, co’a ose i ‘ndéa a cior volta no so ‘ndove e ghe voéa un bèl tóc prima che i tornésse in qua e che i rivésse in cao, màssima se i jèra pareciàdi onti co mezo litro de quel bon tant par farse coràjo. |

These previous singers of the past, when they picked up the Prophecies, in the middle of the choir, in front of the twelve-branched candelabrum, with their voice they went off who knows where, and it was a long clock time before they came spinal column and landed on the grind, specially if they had been previously ‘oiled ‘ with half a liter of the well one [ wine ] just to make courage . |

venetian lexical exports to English [edit ]

many words were exported to English, either immediately or via italian or french. The tilt below shows some examples of imported words, with the date of first base appearance in English according to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary .

| Venetian (DECA) | English | Year | Origin, notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| arsenal | arsenal | 1506 | Arabic دار الصناعة dār al-ṣināʻah “house of manufacture, factory” |

| articiòco | artichoke | 1531 | Arabic الخرشوف al-kharshūf; simultaneously entered French as artichaut |

| balota | ballot | 1549 | ball used in Venetian elections; cf. English to “black-ball” |

| cazin | casino | 1789 | “little house”; adopted in Italianized form |

| contrabando | contraband | 1529 | illegal traffic of goods |

| gadzeta | gazette | 1605 | a small Venetian coin; from the price of early newssheets gazeta de la novità “a penny worth of news” |

| gheto | ghetto | 1611 | from Gheto, the area of Canaregio in Venice that became the first district confined to Jews; named after the foundry or gheto once sited there |

| njòchi | gnocchi | 1891 | lumps, bumps, gnocchi; from Germanic knokk– ‘knuckle, joint’ |

| gondola | gondola | 1549 | from Medieval Greek κονδοῦρα |

| laguna | lagoon | 1612 | Latin lacunam “lake” |

| ladzareto | lazaret | 1611 | through French; a quarantine station for maritime travellers, ultimately from the Biblical Lazarus of Bethany, who was raised from the dead; the first one was on the island of Lazareto Vechio in Venice |

| lido | lido | 1930 | Latin litus “shore”; the name of one of the three islands enclosing the Venetian lagoon, now a beach resort |

| loto | lotto | 1778 | Germanic lot– “destiny, fate” |

| malvazìa | malmsey | 1475 | ultimately from the name μονοβασία Monemvasia, a small Greek island off the Peloponnese once owned by the Venetian Republic and a source of strong, sweet white wine from Greece and the eastern Mediterranean |

| marzapan | marzipan | 1891 | from the name for the porcelain container in which marzipan was transported, from Arabic مَرْطَبَان marṭabān, or from Mataban in the Bay of Bengal where these were made (these are some of several proposed etymologies for the English word) |

| Montenegro | Montenegro | “black mountain”; country on the Eastern side of the Adriatic Sea | |

| Negroponte | Negroponte | “black bridge”; Greek island called Euboea or Evvia in the Aegean Sea | |

| Pantalon | pantaloon | 1590 | a character in the Commedia dell’arte |

| pestacio | pistachio | 1533 | ultimately from Middle Persian pistak |

| cuarantena | quarantine | 1609 | forty day isolation period for a ship with infectious diseases like plague |

| regata | regatta | 1652 | originally “fight, contest” |

| scanpi | scampi | 1930 | Greek κάμπη |

| sciao | ciao | 1929 | cognate with Italian schiavo “slave”; used originally in Venetian to mean “your servant”, “at your service”; original word pronounced “s-ciao” |

| Dzani | zany | 1588 | “Johnny”; a character in the Commedia dell’arte |

| dzechin | sequin | 1671 | Venetian gold ducat; from Arabic سكّة sikkah “coin, minting die” |

| ziro | giro | 1896 | “circle, turn, spin”; adopted in Italianized form; from the name of the bank Banco del Ziro or Bancoziro at Rialto |

See besides [edit ]

References [edit ]

bibliography [edit ]

- Artico, Francesco (1976). Tornén un pas indrìo: raccolta di conversazioni in dialetto. Brescia: Paideia Editrice.

- Ferguson, Ronnie (2007). A Linguistic History of Venice. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki. ISBN 978-88-222-5645-4.

- McKay, Carolyn Joyce. Il dialetto veneto di Segusino e Chipilo: fonologia, grammatica, lessico veneto, spagnolo, italiano, inglese.

- Belloni, Silvano (2006). Grammatica Veneta. Padova: Esedra.

- Giuseppe Boerio (1900). Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. linguaveneta.net (in Italian). Venice: Filippi, G. Cecchini. p. 937. OCLC 799065043. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019.

Read more: Mizuno – Wikipedia